If you’ve been part of a writing team, known a writer, or ever considered documentation to be an important aspect of your business, you may have heard of docs-as-code. If you haven’t, buckle up, because using these methodologies can lower the bar for your developers to contribute quality documentation to your project. At the same time, it also reduces the work your writing team has to do to ensure your documentation meets your company style and standards.

Why docs as code?

The Write the Docs community of technical writers has been exploring the concept of docs as code for years. As a community, they define this concept as

a philosophy that you should be writing documentation with the same tools as code:

- Issue Trackers

- Version Control (Git)

- Plain Text Markup (Markdown, reStructuredText, AsciiDoc)

- Code Reviews

With this philosophy, your writers use the same (or at least similar) tools and workflows as your developers. Your writers can be more easily embedded in your development teams, and can write the first draft of documentation. This speeds final drafts to conclusion.

When your writers and developers are using the same tools, collaboration is faster and easier. Writers and developers can make pull requests against each other’s work, encouraging peer reviews, and consistency.

Linting your prose

Linting is a popular and powerful tool in software development. A software linter checks your code for programming errors, stylistic problems, some bugs, or other problematic constructs. A proper linter can prevent errors from creeping into your working branch, before they get deployed.

One of the newest trends in technical writing is following the same principles - linting your prose. At Write the Docs Portland 2020, and 2019 as well, there were unconference sessions discussing the use of linting in docs as code methodologies. There’s also a dedicated #testthedocs Slack channel in the WTD slack. Prose linters run the gamut of free, open source, closed source, and paid.

Prose linters do much the same that code linters do, but instead of catching code bugs, they catch language bugs - misspelled words, missing Oxford commas, passive voice, missing capital letters, and so on. Anyone who has written anything on a computer has probably used the basic types of linting like the spelling and grammar checkers in products like Microsoft Word or Google Docs. Other tools you may not know about are:

These tools can help your writing teams use the same style of writing, the same voice, and sometimes the same vocabulary. When you’re writing for a blog, you might be most concerned with ensuring that the style remains consistent, but when you’re writing documentation, consistency of terminology is a crucial part of ensuring your users accomplish the tasks they need to complete.

Why I chose Vale

Vale is my personal favorite linter. First introduced in 2018, it’s open source, has maintainers that care, a small but active community of folks contributing to it, and it’s highly customizable. Most important to me in my day to day work: Vale can be run from the command line, or integrated into some popular IDEs (VSCode, Atom).

I prefer Vale over the other linters for several reasons. Hemingway isn’t customizable - I absolutely recommend it for writers who don’t need lots of customization, but it didn’t meet my needs. Grammarly doesn’t have the customizations I need either. Alex.js was close, but not quite enough. Acrolinx is customizable, and has the advantage of being able to define multiple writing voice styles - your marketing and tech writing teams might use the same vocabulary, but they don’t necessarily write in the same tone - but it also comes with a price tag.

What Vale does for me

Vale already has a number of useful features, so maybe the better question is: what does Vale not do for me? Well, it doesn’t do negative look aheads or look behinds, due to the flavor of Go that it’s written in. But it does many other things. Best of all, it uses yaml files for configuration, and extending the information in those files is easy. Some of the tests you can start with:

- Spell checking: You can add exceptions based on my company product names, technical terms, or other words not in the standard spelling dictionary.

- Headings: You can insist that your headers all use sentence case. Product names are usually capitalized though, right? You can tell Vale to ignore those.

- Passive voice: This is a big one - technical writing tends to use the imperative voice, because we’re directing a user to perform an action.

- Gendered text: Vale can help you avoid stereotypes by reminding you to use neutral terms.

- Sensitivity tests: You can add tests to Vale to catch derogatory terms.

Using Vale

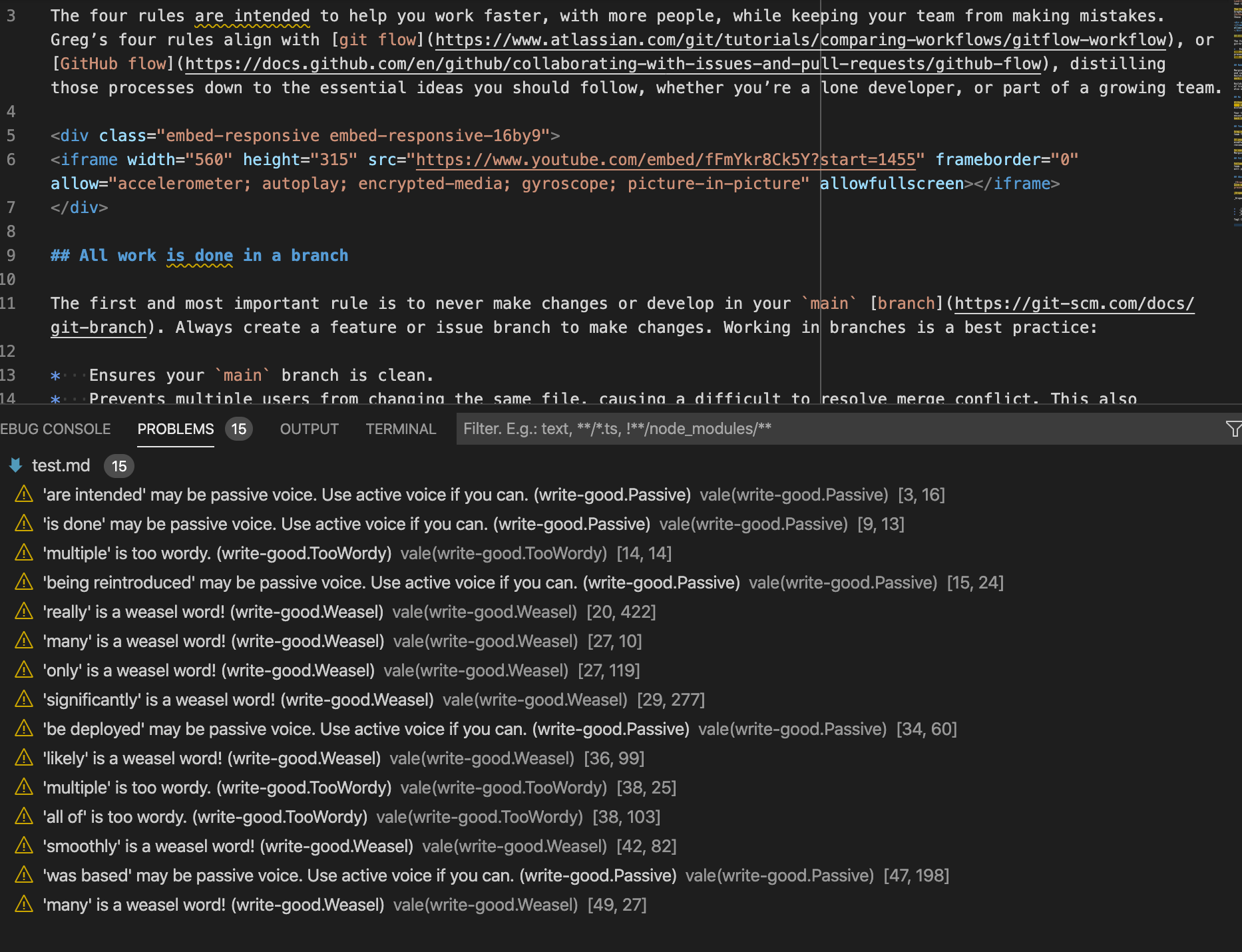

Getting started with Vale is relatively easy. I integrate mine with the Visual Studio Code extension. You can start catching errors right away with just the base tests. For example, I wrote a post: Scaling teams: four rules for faster and safer development. It’s written in (mostly) Markdown, one of the base supported languages. Using the default Vale installation, here’s what I get when I save my file:

At the top is the text, and the bottom frame shows fifteen problems Vale thinks I should consider correcting. In technical writing, writers are expected to be precise, and imperative. ‘Weasel’ words - words that are imprecise - and passive voice are called out.

Make your own style

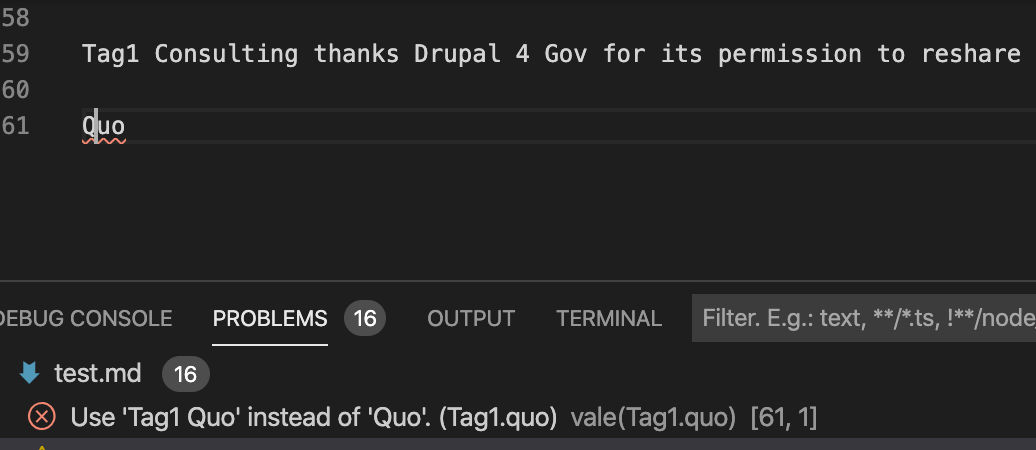

Now you’ve seen what Vale can do by default. I need to customize it for my own use or my company’s use. At Tag1, we have a product called Tag1 Quo. This is the full, proper name of the product, and how it should always appear in any materials. I want to ensure it never slips out as ‘Quo’, even if someone gives me source material with it in there. How do I do that?

-

In the

stylesfolder, create a new directory for the company styles:Tag1. -

Edit the

vale.inifile. Look for the lineBasedOnStyles = write-good. -

Add the new style to the line, separated by a comma. Now it looks like this:

BasedOnStyles = write-good, Tag1 -

Save the

vale.inifile. -

In the

styles/Tag1folder, create a new file:quo.yml. -

This file is based on the vale

substitutionextension point. In the file, add the following, which extends the existing class, provides a message, ignores the case of the text, determines the error level, and shows what text is being changed:extends: substitution message: "Use '%s' instead of '%s'." ignorecase: true level: error swap: quo: Tag1 Quo -

Save the file.

When Vale is used on a file with the incorrect word, an error displays:

This isn’t the best test, because of the look-ahead/look-behind issue, but it is an example of how a substitution test works. Customize your own tests for what you need.

In summary

Linting is as powerful for writers as it is for developers. As documentation manager Craig Norris says, “We are communication engineers, whose codebase is a docset.” Prose linting can be incorporated into your writer’s workflow, your developer’s workflow, and can even be turned into a GitHub action, helping your teams ensure your documentation meets standards before merging a PR. Just like code reviews, documentation reviews ensure your success, and that of your customers. Automating these reviews where you can helps your writing team focus on the bigger questions your documentation needs to solve, reducing time spent on the small, easy to miss edits.

Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash